I’ve been missing a continuation of Cryptopals after I finished Set 8. Here I make a humble attempt at starting to define new problems and solving them. I hope you enjoy them.

Table of Contents

- Challenge 67. Rainbow tables: space efficient recovery of passwords from their hashes

- Challenge 68. Multiplicative ElGamal with elliptic curve groups (simple version)

- Challenge 69. Multiplicative ElGamal with elliptic curve groups (Elligator 2-based version) and a small subgroup attack

- Challenge 70. Weaknesses in Dual Elliptic Curve Deterministic Random Bit Generators (aka DUAL EC DRBG)

Challenge 67. Rainbow tables: space efficient recovery of passwords from their hashes

In addition to the properties of second preimage resistance and target collision-resistance, which we looked at in

Challenges 53 and 54, another popular use for hash functions relies on their one-way property.

Namely given y = H(x) it should be computationally infeasible to derive x. This property of cryptographic

hash functions is used in identification and login protocols such as those found in various Unix systems.

In the simplest form the identification system will use a table such as one shown below to verify that the user logging in indeed knows their password.

| user-id | Hash |

|---|---|

| id1 | H(password1) |

| id2 | H(password2) |

| … | … |

| idn | H(passwordn) |

Not storing a password in plaintext presumably makes it harder to figure it out by coming

in possession of the passwords file. Assuming passwords are n characters long where each character is one of the 95

printable ascii characters, one would think that an attacker getting hold of such a file will need to do an exhaustive

search on each user’s password to discover it, which requires an effort of O(95n) per password.

For such a primitive system an active attacker can even pre-compute hashes for all n characters passwords and store them

in an dictionary table L. Then, every time the attacker intercepts a user’s login password hash, they are able to immediately

look up their password in table L by the hash. This is known as an offline dictionary attack. The total effort required to build

such a table is O(95n). The total space will be 95n · (32 + n) bytes. For 8 character passwords hashed with

SHA-256 this will take up around 32 PiB, which is not practical. Can we do better? It turns out we can thanks to

Hellman’s basic time-space trade-off, which was later evolved into what is now known as rainbow tables.

The idea of a rainbow table is fairly simple. Say your passwords occupy space Ρ and their hashes space ϒ. The hash function h, e.g. SHA-256, then maps elements in Ρ to those in ϒ — h: Ρ → ϒ. Note that the size of ϒ (2256 bits for SHA-256) is larger than the size of Ρ (< 264 for 8 character passwords). The first thing to do to build a rainbow table is to come up with a function that provides an inverse mapping, i.e. a mapping from elements in ϒ to Ρ. Let’s call this function y: ϒ → Ρ. The simplest way to construct it is to take the minimum number of the most-significant bits from a SHA-256 hash that are required to represent 8 ascii symbolds and convert these bits into ascii symbols.

The next step is to come up with a way to make multiple such y functions, each one behaving differently. Let’s assign them an index so that we refer to them as yi. How do you make them behave differently from the original y function in the previous paragraph? You can generate a unique random pad for each i and then define yi(hash) as:

y(i, hash) := to_ascii_array(most_significant_bits_of(hash) ^ random_pads[i])

Or you can make it even simpler and do something along the following lines:

y(i, hash) := to_ascii_array(to_long(most_significant_bits_of(hash) + i))

this way no storage for random pads is called for.

With our yi: ϒ → Ρ ready let’s define another group of functions called fi as follows: fi(x) := gi(hash(x)). If you’ve been paying attention, you’ve noticed that fi map elements in Ρ to elements in Ρ (e.g. from 8 character ascii passwords to 8 character ascii passwords).

The next thing we do is define the number of rows (l) and columns (τ) in our rainbow table L. If |Ρ| = N,

then we define l = N2/3 and τ = N1/3. You might want to take a ceiling of these exponentiations to ensure that l·τ >= N.

Now we are ready to build our rainbow table L. For each row you generate a random 8 character password and then

map it to another password with f1, which you then map with f2 into yet another password, etc. until after applying fτ you get the

final password for the first row which I call z1. Then you put the pair (z1, pw1) into a hash map (you don’t need to store

all elements of the rainbow table, for each row it suffices to represent the first and last only so a hash map is a good fit).

Then you proceed with the second row and do exactly the same as for the first. Before putting (z2, pw2) into your hash map,

you need to check if there’s already an element with the same key value as z2 there. If not, all is well and you just proceed

to store (z2, pw2) in the hash map. if there’s already a key with the same value as z2, you generate another value for pw2 and try

deriving all passwords from the second row again. Repeat until you get to (z2, pw2) where z2 is not present in the hash map.

Do the same for the remaining rows. At the end your hash map will contain l (zi, pwi) pairs where

each zi is unique. Actually, if you give it some thought, you will notice that the above also ensures that

all pwi’s are also unique. The below picture illustrates the process:

pw1 * f1 -> * f2 -> * f3 -> ... fτ * z1

pw2 * f1 -> * f2 -> * f3 -> ... fτ * z2

...

pwl * f1 -> * f2 -> * f3 -> ... fτ * zl

The total space required to store the hash map for the rainbow table to recover 8 character ascii passwords from their SHA-256 hashes is just a few hundred GiB. Contrast this with a few PiB of storage one would need if they tried to build a table for mapping all 8 character passwords to their SHA-256 hashes.

With you hash map for the rainbow table constructed, you are now ready to intercept password hashes and quickly recover

their passwords. The algorithm to do it is fairly simple. Therein L_hash_map refers to the hash map that was introduced above,

yi(h) is denoted as y(i, h), likewise fi(z) is designated as f(i, z):

recover_password(h):

z := y(τ, h)

for i from τ-1 to 1:

pw := L_hash_map[z]

if pw != None:

for j from 1 to i:

pw := f(j, pw)

if hash(pw) == y:

return pw

else:

z = g(i, h);

for j from i+1 to τ:

z = f(j, z);

return None

Assuming a system that uses 5 character long ascii passwords, given the following three MD4 hashes:

C89F2A956A8C8AE1F3D2B547BDA4498F

27300880ECECAAF7FF6705F10C6BC35F

8D850E3B2E28233C24432FCF45372B74

build a rainbow table and recover the original passwords. The base64 encodings of the original passwords are as follows (no peeking please):

clx4IDw=

KTlpMGg=

Il44LC4=

Keep in mind that the probability of the rainbow table containing the password you are looking for is around 63% so you might need to build a couple of different rainbow tables to recover all the three passwords.

How do you protect your system from being vulnerable to such attacks? By ensuring that for each password there’s also a unique salt value created from a large enough space. The identification system will then use a table with an additional column to authenticate the user logging in:

| user-id | Salt | Hash |

|---|---|---|

| id1 | salt1 | H(salt1 || password1) |

| id2 | salt2 | H(salt2 || password2) |

| … | … | … |

| idn | saltn | H(saltn || passwordn) |

Challenge 68. Multiplicative ElGamal with elliptic curve groups (simple version)

The RSA encryption system you implemented in Challenge 39 and its various incarnations — PKCS#1 mode 2 v1.5, v2.0 (OAEP), v2.1, v2.2 — is not the only public key encryption algorithm. Another popular approach is called multiplicative ElGamal. It’s inspired by the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol.

Here’s how it works. Imagine you have a cyclic group G of prime order q with a generator g, which can be a group of points on an elliptic curve.

Alice computes her private key α by generating a random number from set Zq. Alice’s public key is υ = gα, which she makes publicly known.

Bob, who wants to send a secret message m (that can be mapped to G) to Alice, carries out the following actions:

- Encodes m (which we’ll assume to be l bits long) as an element of G, the result of the encoding is menc ∈ G.

- Generates a transient private key β as a random number from Zq and the corresponding public key ν = gβ.

- Encypts menc as follows c = υβ · menc

- Sends Alice the pair (ν, c)

Alice then decrypts the c as follows:

- Computes menc = c / να. NB: menc ∈ G, and thus is an elliptic curve point if G is an elliptic curve group

- Decodes menc into the original l-bits long message m.

Sounds trivial, doesn’t it? However if you try to implement it for elliptic curve groups such as the ones you tackled in Challenge 59 and Challenge 60, you will quickly realize how non-trivial mapping arbitrary l-bits long messages to points on an elliptic curve group is. Moreover the mapping needs to be efficiently invertible. One naïve approach would be raising the group generator to the power which is the integer representation m. However getting to the pre-image would then call on taking a DLog in E(Fp). Are there any useful reversible mapping functions for E(Fp) groups?

Yes, there are. In this challenge we’ll look at a simple construction that is fairly generic and improve on it in the next challenge. We start with solving the invertible mapping problem for elliptic curves in the short Weierstrass form. These curves were introduced in Challenge 59. To remind: an elliptic curve E(Fp) in Weierstrass form is defined as

y2 = x3 + a·x + b

The total number of points on this curve is p + 1 − t, for some integer t in the interval |t| ≤ 2√p. In other words it’s approximately p. So an optimal algorithm should allow us to map l-bit long strings where log2(p+1-2√p) <= l <= log2(p+1).

The encoding algorithm we start with (due to Fouque, P.-A., Joux, A., and Tibouchi, M.) is more humble. It allows to encode messages of up to 1/2·log2(p) bits long. The encoding function F: {0, 1}l → E(Fp) works as follows.

To compute F(m), pick a random integer x in [0, p − 1] whose least significant l bits coincide with m. If there are points in E(Fp) of abscissa x mod p, return one of those (at most two) points; otherwise, start over. The inversion algorithm I then simply maps a point (x, y) ∈ E(Fp) to the bit string m formed by the l least significant bits of x.

With a correct choice of l, the expected number of iterations in F on any input is less than 3.

Implement multiplicative ElGamal for curve secp256k1. The order of secp256k1 is prime, so this elliptic curve group is fine to use for multiplicative ElGamal.

Let l be 127. Given the following Alice’s public key:

WeierstrassECGroup.ECGroupElement(x=ad9cfab1e08e1083cf7956726c02a335672df4f5bf69fce97beb3f649a705e23, y=82d9b937dc354fd32a2d4ff8fba4f1138d954d5797da79215c43793043eaf0ad)

send her a few 127-bits long messages. Verify that Alice is able to correctly decrypt them. The Base64 encoding of her private key is:

AJNqDTV/2WuxT8V8eC7Je4NNEHmfT/gbhZbW57G+0ILB

Word of caution. While providing Chosen-Plaintext Attack (CPA) security, i.e. secrecy in the face of a passive attacker, multiplication ElGamal is not Chosen-Ciphertext Attack (CCA) secure and will not hold up to an active attacker who can manipulate ciphertext messages. It is possible to combine ElGamal encryption with a CPA-secure symmetric cypher such as the AES in the counter mode to achieve CCA security, which we will tackle in a later challenge.

Challenge 69. Multiplicative ElGamal with elliptic curve groups (Elligator 2-based version) and a small subgroup attack

In this challenge you will learn how to:

- efficiently map elements of Fp onto a subset of Montgomery elliptic curves and back

- make use of such a map to implement multiplicative ElGamal over the popular Curve22519

- recover a few bits of the plaintext if Multiplicative ElGamal wasn’t used correctly.

Let’s start with the Fp <–> E(Fp) map. To construct one we first need to dabble into the

concept of square roots in Fp. Elements of Fp for which a square root exists are called quadratic

residues modulo p. The total number of quadratic residues in Fp is (p-1)/2 + 1. Obviously if

s is a square root of x mod p, then so is -s (i.e. p-s mod p). The famous Legendre symbol can be used to test if

x is a quadratic residue mod p: x(p-1)/2. If it computes to 1, then x is a quadratic residue. If it computes

to -1, then x is a quadratic non-residue modulo p. If it computes to 0, then p divides x (i.e. p|x).

Square roots in Fp

While figuring out whether a square root of x exists in Fp is trivial, calculating it is a little more involved. Since we are dealing with primes greater than 2, there are two cases — 1) p mod 4 = 3, or 2) p mod 4 = 1. Let’s start with the first. In this case the square root of x can be calculated as: r = x(p+1)/4. Both r and -r are the square roots of x. Moreover, r is the so-called principle square root (which is a fancy way of saying that it’s also a quadratic residue.

The case where p mod 4 = 1 is more tricky and can be subdivided into two: 1) p mod 8 = 5 and 2) p mod 8 != 5. The second calls for the Tonelli–Shanks algorithm. Fortunately in this challenge it will suffice to cover the case of p mod 8 = 5, which can be calculated as follows:

- Compute d = x(p−1)/4 mod p.

- If d = 1 then compute r = x(p+3)/8 mod p.

- If d = p−1 then compute r = 2x(4x)(p−5)/8 mod p.

- Return (r, −r).

Why the special case for d=p-1 (i.e. d=-1)? For d=-1, choosing r = a(p+3)/8 mod p would lead to r2=x⋅d=-x. So we need to multiply x(p+3)/8 by the square root of -1 to get r2=x. What is √x mod p? When p mod 8 = 5, 2 is a quadratic non-residue mod p, i.e. 2(p-1)/2 = -1. Therefore √x = 2(p-1)/2. Multiplying x(p+3)/8 by 2(p-1)/2 mod p yields exactly 2x(4x)(p−5)/8 mod p.

Injective map from the elements of Fp to E(Fp)

In general such maps cannot be constructed for any elliptic curve. In this challenge we will use the map called Elligator. It works for cyclic elliptic curve groups that are subclasses of Edwards and Montgomery curves. Given that we’ve already mastered Montgomery curves in Challenge 60, we will use a map that works with some of them. What kind of Montgomery curves are amenable to constructing such an injective map? All cyclic elliptic curve E(Fp) groups in the following form v2 = u3 + A·u2 + u are. The injective map for such curves is called Elligator 2. You can read all about it in this paper. Such a map requires two parameters: a function for calculating square roots mod p (which I already explained above) and a small non-residue mod p called u. In case p = 3 mod 4, you can take u = -1 (i.e. p-1). If p = 5 mod 8, you can take u = 2. If your p doesn’t fall under any of these two cases, just search for one starting from 1.

The map takes an integer from the set { 0, 1, …, (p−1)/2 } and maps it onto elements of E(Fp). It works as follows:

function map_from_Fp(r):

if r <= p/2:

return None # r too large

r_squared_times_u_plus_1 = r^2 * u + 1

if r_squared_times_u_plus_1 % p == 0 or A^2*u*r^2 == r_squared_times_u_plus_1^2:

return None # r not mappable

v = (p - A) * mod_inverse(r_squared_times_u_plus_1, p)

e = legendre_symbol(v^3 + A*v^2+ v, p)

x = e*v - (1-e) * A * mod_inverse(2, p)

y = (p - e) * square_root(x^3 + A*x^2 + x, p)

# Montgomery curve point (x, y)

return (x, y)

Inverting the map can be done pretty eloquently too:

function modulo(x, p):

'''

Computes x if x belongs to set { 0, 1, ..., (p-1)/2 }, otherwise -x.

'''

return x if x <= p/2 else p - x

function map_to_Fp(curve_point):

x, y = curve_point

# Check if mappable

if y==0 and not x==0 or x==A or legendre_symbol((p-u)*x*(x+A), p)==1:

return None

if y == square_root(y^2%p, p):

return square_root( (p-x) * mod_inverse((x+A)*u, p), p)

else

return square_root( (p-(x+A)) * mod_inverse(u*x, p), p)

Curve25519

Curve25519 is designed to be twist secure. It is defined over the prime p=2255 − 19, hence its name.

This p is the largest prime less than 2255 and this enablesbfast arithmetic in Fp.

For this prime we have p mod 8 = 5, which makes for efficient computation of square roots in field Fp.

Curve25519 presented as a Montgomery curve is simply

v2 = u3 + 486662·u2 + u. The curve has a cofactor of 8 (i.e. the number of points on

this curve is eight times a prime). The largest cyclic subgroup of this curve of prime order is generated by a point

P = (u1,v1) where u1=9. This is the canonical generator of this subgroup.

This subgroup has an order of 2252 + 27742317777372353535851937790883648493.

The order of the whole group is 8 ⋅ (2252 + 27742317777372353535851937790883648493). The whole group is also cyclic and can be generated by the following generator (it’s one of the many, let’s agree to call it g1):

MontgomeryECGroup.ECGroupElement(u=6388931193617442843730615974211913565219356972986535115281385604017080356929, v=15183578202947452771374813110749360144330333520376073491257004066936409973672)

Implement Multiplicative ElGamal over curve25519, using Elligator 2 to map plaintext messages to curve25519 points. You should be able to encrypt messages of up-to 31 bytes long. Ensure that the generator for computing public keys is the base point u=9. Given the following Alice’s public key:

u=MontgomeryECGroup.ECGroupElement(u=6151694642649833976868439641848642547760628665844455140404152921880181572779, v=56709348787383946544741429006065123623725150943461932328001646618258711393463)

send her a few 31-bytes long messages. Verify that Alice is able to correctly decrypt them.

The Base64 encoding of her private key is: BFfz1Bh/zSndeZoJehuXva9RuuC6HZ0fcumX7DqUCCY=.

Small subgroup attack on Multiplicative ElGamal

Remember my mentioning that Multiplicative ElGamal must be defined over a cyclic group of prime order? There’s a good reason for this, which is known as the decision Diffie-Hellman assumption. Multiplicative ElGamal is semantically secure in groups where the decision Diffie-Hellman assumption holds. Unfortunately it holds only for cyclic groups of prime order.

So what happens if we implement multiplicative ElGamal over an elliptic curve group of primary order (which in the case of Curve25519 is the subgroup G generated by the base point u=9) but mistakenly use it to encrypt a plaintext message that Elligator 2 maps to a curve point that is not member of the primary order subgroup generated by the base point u=9 but by a generator producing the entire curve group G1? This can easily happen for Curve25519 given that it has a cofactor of 8 and that Elligator 2 doesn’t attempt to restrict to points on the primary order subgroup. Let’s look at this situation in more detail. You will recall from the previous challenge that the ciphertext for multiplicative ElGamal is c = υβ · menc, where υ is Alice’s public key. υβ ∈ G, as we expect. However menc ∈ G1 (the whole group, which is not of primary order). As a result the ciphertext c = υβ · menc ∈ G1 instead of ∈ G. Let’s scale c to the order n of G and see what happens:

cn = υβ·n · mencn (1), where n is 2252 + 27742317777372353535851937790883648493

since scaling an element of a group to its order gives an identity element, we have:

cn = mencn (2)

Now since menc is member of the whole group of Curve25519, it can be produced raising the generator g1 of the whole group to some power γ, i.e. menc = g1γ. Substituting it into (2) yields:

cn = g1γ·n (3)

By Lagrange theorem we know that mencn is bound to be in a group with max 8 elements. This makes it trivial to learn the 3 lowest order bits of γ, which indirectly gives you 3 bits of knowledge about menc. Implement logic to figure out the 3 lowest order bits of messages encrypted with Multiplicative ElGamal where Elligator 2 is used to encode plaintext messages to curve points and menc ends up ∈ G1.

You can find my solution to this challenge here:

Challenge 70. Weaknesses in Dual Elliptic Curve Deterministic Random Bit Generators (aka DUAL EC DRBG)

Generating random bits is critical in cryptography. We rely on secure pseudo random generators (PRNG) to generate keys, initialization vectors, random challenges in identification protocols, to sign with DSA or RSA, etc. Things will run amok when a pseudo random generator you use is not cryptographically secure. What makes a PRNG cryptographically secure? Basically two things: 1) the PRNG must be indistinguishable from a truly random generator, and 2) it must be unpredictable in the sense that no matter how many random bits of its output you’ve observed, you are not able to predict the next bit.

There are many different secure PRNGs around, in this challenge we will examine a former NIST-standardized Dual Elliptic Curve PRNG. It has gained notoriety because of a security breach that it contributed to — the Juniper hack. The Juniper product that was targeted was a popular firewall device called NetScreen, whose ScreenOS software made use of this Dual EC PRNG.

History aside, let’s look at Dual EC PRNG. In this challenge we’ll use the Dual EC 2007 version. Dual EC PRNG makes use of a NIST standardized curve called secp256r1 (aka P256). The curve has the standard Weierstrass form:

y2 = x3 - 3·x + b

where b in hexadecimal is: 5ac635d8 aa3a93e7 b3ebbd55 769886bc 651d06b0 cc53b0f6 3bce3c3e 27d2604b. The curve P256 is defined

over the prime p = 2256 − 2224 + 2192 + 296 − 1. The order of the group of

points on this curve, let’s call it r, in hexadecimal is ffffffff 00000000 ffffffff ffffffff bce6faad f3b9cac2 fc632551 and is a prime number.

The order of this elliptic curve being prime has important implications that are used by this generator:

- This elliptic curve group has a co-factor of 1, which is an elaborate way of saying that it has no non-trivial subgroups.

- All the group elements except for the point at infinity are generators.

Why the adjective dual in the name of this PRNG? It’s because it makes use of two predetermined points on this curve for its work. They are called P and Q. NIST came up with recommended values for them:

P=(6b17d1f2 e12c4247 f8bce6e5 63a440f2 77037d81 2deb33a0 f4a13945 d898c296, 4fe342e2 fe1a7f9b 8ee7eb4a 7c0f9e16 2bce3357 6b315ece cbb64068 37bf51f5)

Q=(c97445f4 5cdef9f0 d3e05e1e 585fc297 235b82b5 be8ff3ef ca67c598 52018192, b28ef557 ba31dfcb dd21ac46 e2a91e3c 304f44cb 87058ada 2cb81515 1e610046)

At the same time the standard allows to use alternate values of P and Q, albeit it doesn’t recommend it. Remember that I highlighted that the property of the curve is that all its elements are generators? This means that there exist values:

- e=logPQ (i.e., the integer e such that e·P = Q); and

- d=logQP=e−1 mod r, where r is the order of the group

If you know either e or d, you can go far at breaking the unpredictability property of this PRNG provided you get to see a full block of its output. NIST never revealed them for the standard recommended P and Q, no one knows for sure if NIST or NSA even know them. But I am getting ahead of myself here.

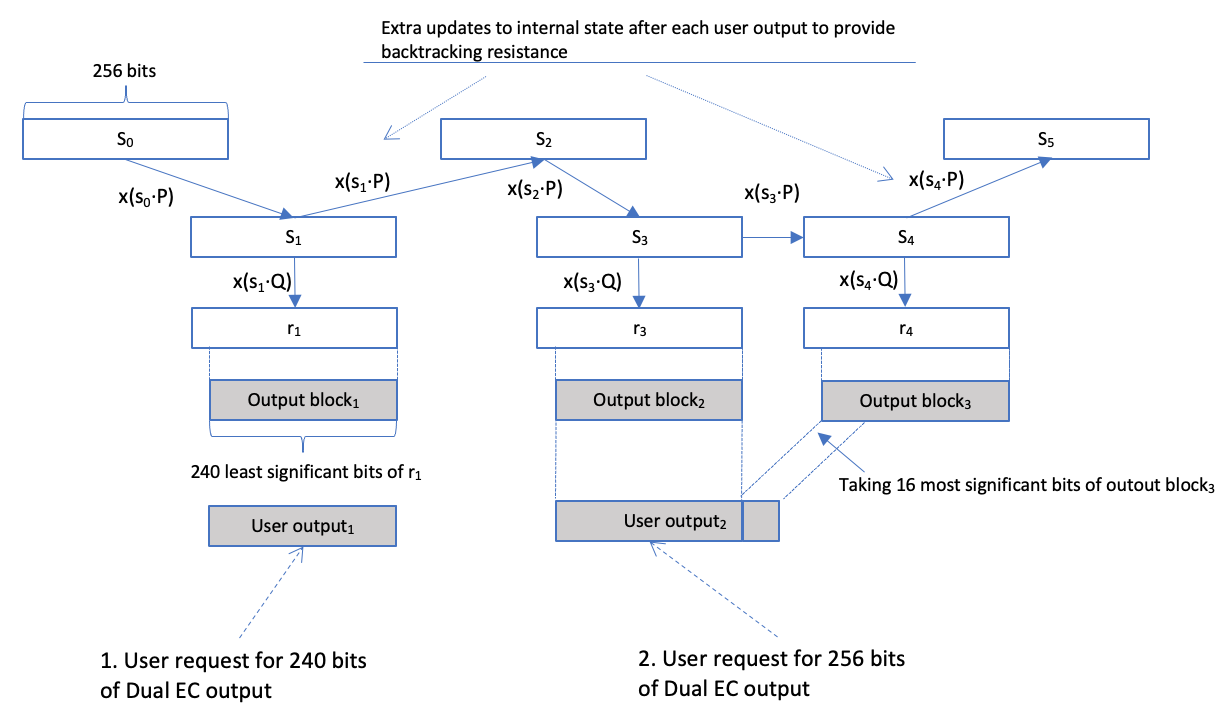

The schematic representation of Dual EC is captured in the picture below:

It has an internal state denoted as si, which is 256-bits long. The internal state gets modified after generating each block of output. The modification is pretty simple si+1 = x(si·P). Essentially we are producing another point on the curve by scaling P to si and then taking the x coordinate of the new point. How does s0 get initialized? It is supposed to be initialized to a random string that has ideally 128 bits of entropy or more, using available sources of randomness. For the purposes of this challenge we will initialize it using the platform’s default secure PRNG (Fortuna on my macOS 11.5.2).

Output blocks ri are produced from the internal state by scaling point Q to si and then taking the x coordinate of the new point. Only the 240 least significant bits of the output are passed on to the user. If the user requests more than 240 bits, say 256 bits as I depicted in the figure, then the PRNG produces a second output block of 240 bits and takes the 16 most significant bits out of them.

After processing each user request the Dual EC 2007 algorithm additionally updates the internal state si+1 = x(si·P). This is meant to provide backtracking resistance i.e. to prevent working backwards from the internal state to earlier random numbers.

After generating 232 ri blocks, the internal state s should be reinitialized from the available sources of entropy, pretty similar to how s0 was produced.

With all of this explained go ahead to implement Dual EC PRNG. Make sure that when your PRNG is initialized you can supply it with a Q point of your choosing. Please test its output on not being distinguishable from the uniform distribution using χ2. I generated 3000 integers in the range [0, 51), i.e. 51 categories. For the uniform distribution the expected frequency of seeing each category is p=51/3000. If your resulting χ2 is less than p95 = 67.5, you are good. If higher, you likely have made a mistake as the probability of witnessing such a run with a uniform PRNG is less than 5%.

Now that you have built and fine-tuned the PRNG, we can mount the actual attack on its alleged unpredictability. This is

only possible if you come up with your own Q. So generate a random exponent e (up till r — the order of the EC group),

find its inverse d, and finally produce point Q:

e := random(100, r)

d := inverse(e, r)

Q := scale(P, e)

Instantiate your Dual EC PRNG with this Q and request 32 bytes of output from it. Break this up into two pieces: one containing the first 30 bytes and the second containing the last two. You will recall that these 32 bytes were produced from two separate output blocks of your DUAL EC PRNG, namely r1 and r2. So the first 30 bytes constitute the 240 least significant bits of r1. Iterate through every possible 216 most significant bits of r1 (that you don’t know) and prepend them to arrive at the whole r1’ candidate. Roughly half of the r1’ values will be valid x-coordinates of point R1:=s1·Q. For each such R, compute s2′ = x(d·R1) and r2′ = x(s2′·Q).

The key insight is that multiplying the point s1·Q by d yields the internal state x(d·s1·Q) = x(s1·P) = s2.

Now go to the last 2 bytes of your call to the PRNG and search among the r2′ candidates for those whose bits 240:224 correspond to the last 2 bytes of the PRNG. The corresponding s2 is the correct internal state of the PRNG. NB: Since you are matching 240-bit outputs by only 16 bits, there’s a small probability that you will wind up at 2 (max 3) candidates for the internal state. Deal with it.

Go ahead to construct a second PRNG with the same Q and internal state you’ve recivered and verify that they produce the same output. Bingo! You have uncovered the crux of what happened to Juniper’s NetScreen product. A group of attackers were able to modify the sourcecode of its OS to implant the Q point of their choosing.

You can find my solution to this challenge here: